Braille Dots

Braille History , New York Point and related technologies.

The History

Author: Tim Böttcher – 07/26/2020

Access to communication in the widest sense is access to knowledge, and that is vitally important for us if we are not to go on being despised or patronized by condescending sighted people. We do not need pity, nor do we need to be reminded we are vulnerable. We must be treated as equals – and communication is the way this can be brought about.

Louis Braille

Braille, the print for the blind. It’s the gateway to most interactions between my environment and me. Without it, I could neither work, nor write this article. But who invented braille, what were the alternatives, how did it become the standard print for the blind and what are related technologies?

This article gives you an overview.

The events leading up to the invention of braille surely were a tragedy for the Braille family. Louis Braille, born on January 4th 1809, was playing in his father’s workshop when his life changed drastically. His father was a successful leather worker and Louis played with one of his awls, trying to poke holes into a piece of leather. The awl, however, glanced off of the leather and struck Louis’ eye, wounding it badly.

Though the family tried to reach out to a surgeon, the damage was beyond repair. Worse still: The wound got severely infected, the infection spread to his other eye, and in the course of the next two years, Louis lost his sight completely. He was only five years old at that time.

The Braille family didn’t give up, though. His father made canes for Louis with which he learned to navigate his home village and its surroundings. He attended classes in his village and even though he could only listen, he managed to impress his teachers. So when he was ten years old he went to one of the world’s first school for the blind in Paris.

There, he soon got confronted with a problem: Reading books was very hard work for people with vision impairments. The founder of the school, Louis, went to Valentin Haüy, who developed a system of embossing letters on thick paper such that the students could feel them and decipher the books’ content. But these books were extremely heavy and required a lot of focus and time to read. Besides, it was very expensive and complicated to produce the books, and blind people couldn’t write that way at all. It was without doubt an important step towards unlocking print for the blind, but it was a one-way communication system, so it only did half the job.

Hence, Louis began looking for better ways of presenting print to the blind. He learned of a system developed by Captain Charles Barbier called night writing. Barbier originally developed it for the French military so soldiers could exchange messages in the dark without needing light nor verbal communication.

But the night writing system proved to be too complex – however, Braille adapted and optimized it for the blind.

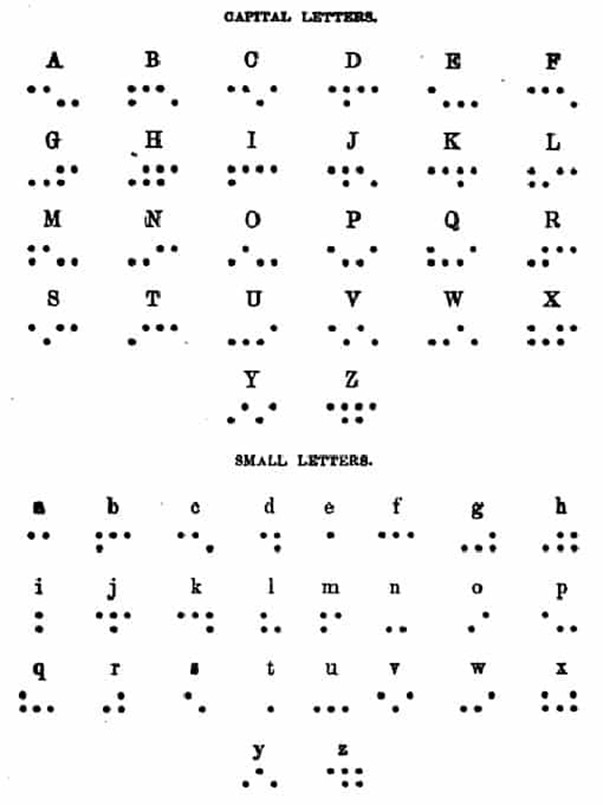

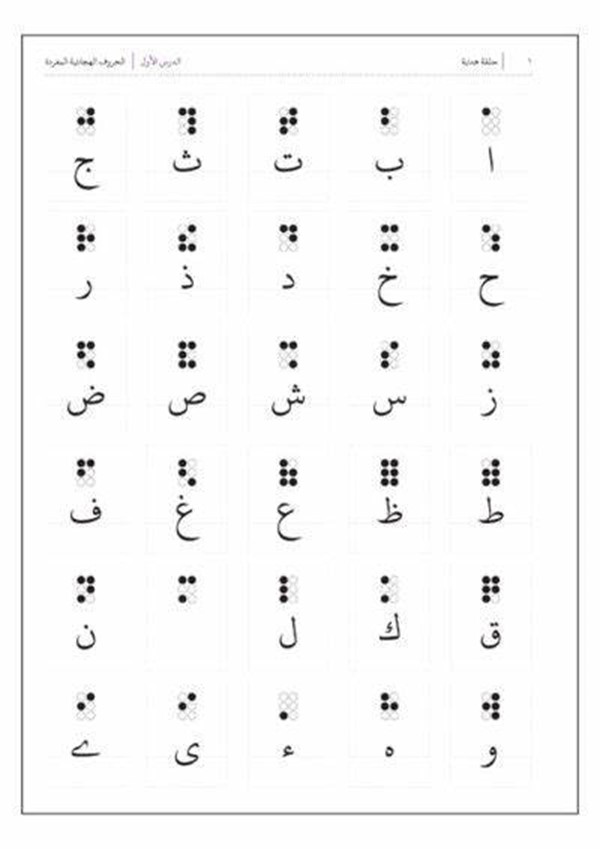

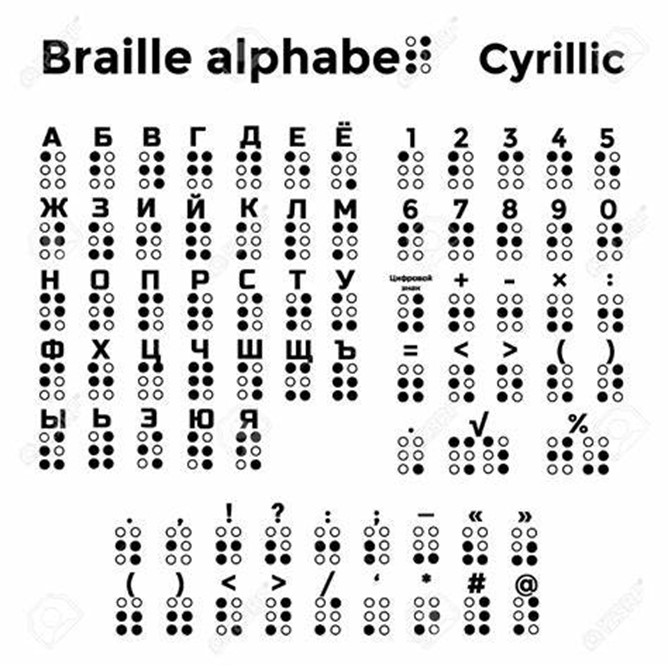

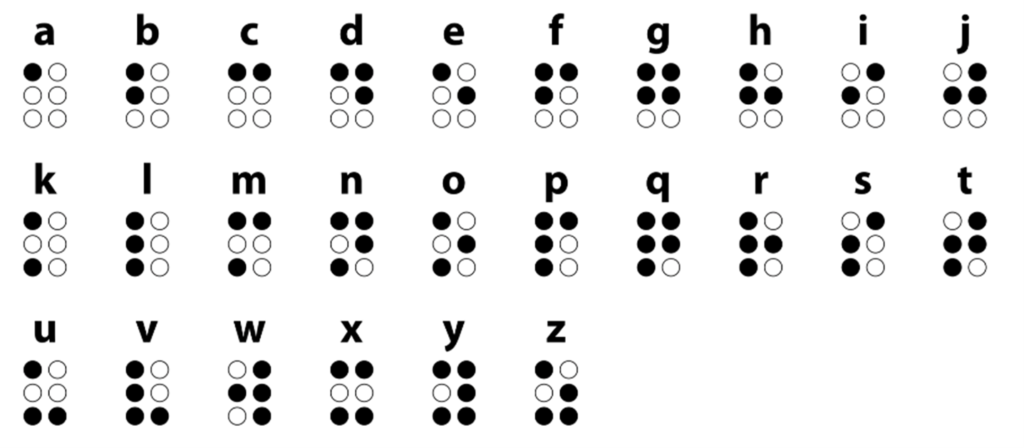

In traditional braille, each letter from a to z gets represented by a single block and each block contains two columns of three dots, so six dots overall. Depending on which dots show in which column, a different pattern of dots appears, representing different letters and symbols. The representation of special symbols such as numbers, punctuation, or ä, à, @, etc. differs across different languages, but the representation of the letters a to z remains the same across all languages that use Latin letters.

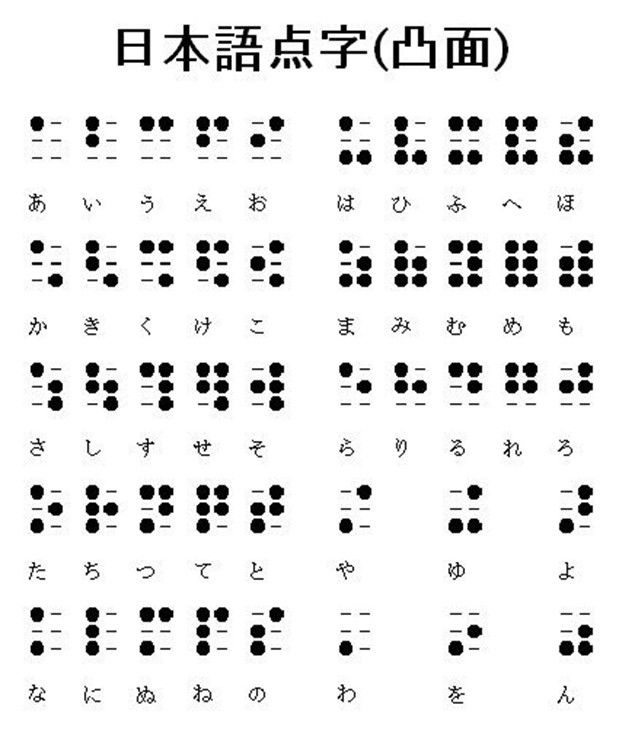

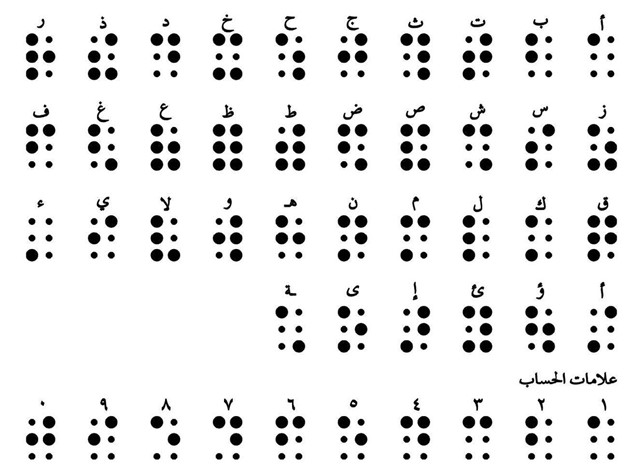

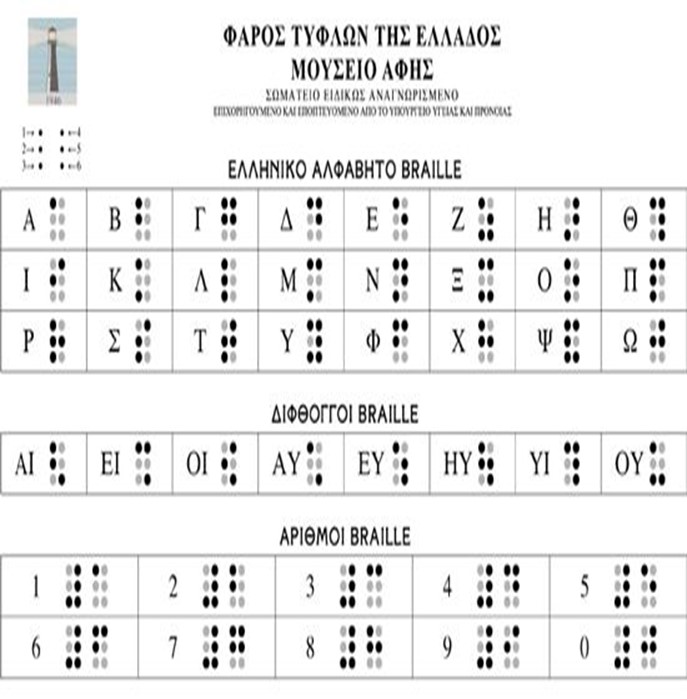

Languages such as Japanese define the dot combinations and their meaning completely differently than languages that use the Latin alphabet; the basic concept as developed by Louis Braille remains virtually unchanged all over the world, though.

As mentioned before, braille ultimately became the international standard, even in languages which don’t use the Latin alphabet. This success wasn’t uncompeted though. The New York Point System got invented in 1868 by William Bell Wait. It also derived from night writing, but used two rows with four dots each instead of two columns with three dots each.

While the rest of the world mostly adopted the braille system, the New York Point System was the standard for American schools well into the 20th century. But it had one major disadvantage in comparison to braille: You needed more than just one finger tip to read a single letter, since these letters got much too wide for just one finger tip.

Though braille and the New York Point System unlocked easy reading to the blind and made production even of larger books feasible, the process of writing both prints remained complicated, and that’s what most innovations focused on in the first decades after the prints’ invention.

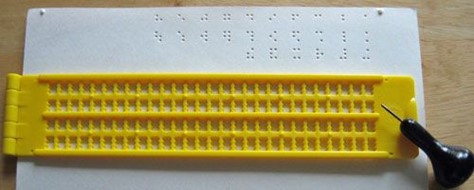

Originally, the raised dots of braille were produced using a slate with indentations to match the six dots per block and a stylus used to emboss the dots on a piece of (thick) paper laid across the slate. The stylus got pressed on the paper such that it fit into one of the indentations, thus creating a raised dot on the other side of the paper. Due to the nature of this process, one needed to write from right to left and mirror-inverted to create text that was left to right and spelled correctly on the other side of the paper. For instance, to create the letter o (dot 1, 3, 5), the writer had to write dots 2, 4, 6 on the other side of the paper. Naturally, this was less than ideal and made fast writing difficult. Nonetheless, the slate and stylus still get used by some blind people to e.g. take notes when electronic devices fail because they aren’t as heavy or noisy as braille typewriters.

The first machine which could pass as a braille typewriter got created by Frank Haven Hall in 1892.

The Hall Braille-writer 1 proved to be a significant improvement to writing braille. The machine had six keys, one for each dot. Users could write any braille letter by pressing different combinations of these keys, as opposed to writing a letter dot by dot. Additionally, the needles creating the dots were below the paper, removing the need to write from right to left and mirror-reversed. Naturally, this made writing texts in braille a lot more enjoyable and faster. It’s worth noting that the Hall Braille-Writer got sold just above production cost: The production cost was $10, and it got sold at $11.

Mr. Hall’s Braille-Writer may have been the first typewriter for the blind, but it didn’t stay the only one for long. In 1894 Mr. Wait invented the Kleidograph, a typewriter for his New York Point System. It had eight keys for the eight dots, and two more keys which each pressed down four keys at once, which meant that it was possible to use the typewriter with only one hand – the first and only typewriter for the blind with that capability. But when New York Point System got discarded, the Kleidograph went out of service as well.

©The Martin Howard Collection – antiquetypewriters.com

Another improvement to braille typewriters was the Perkins Brailler, invented in 1951. Its major advantages over other braille typewriters include its reliability, resilience and the fact it had a backspace and line feed key, something the Hall Braille-Writer lacked. It was both (relatively) affordable for the public and required little repair to keep working, leading to widespread usage.

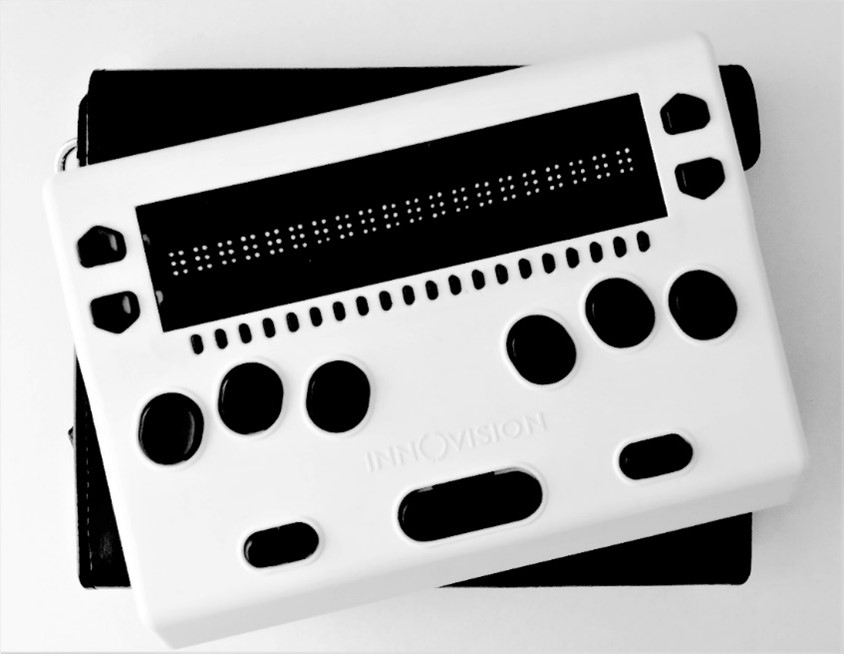

Braille Me from Innovision

When people hear of refreshable braille displays for the first time, their first reaction often is to say, “Wow, that’s science fiction right there!” Funnily enough, the first electronic device with a refreshable braille display got released in 1975. But what even is a braille display, and what makes it so important?

When computers started re-shaping the world, blind and vision impaired people were once again excluded. The main problem was that braille was only static: It didn’t change in accordance with the state or content of a screen. You might wonder why people even bothered with making braille dynamic since just speaking content onscreen is seemingly enough. But there are situations, like when writing books, articles, research papers etc., where you want to be able to immediately check your spelling without too much of a hassle. In coding, being able to see the formatting of a code snippet can be helpful, or might even be required (e.g. in Python). So there are valid reasons for creating refreshable braille displays.

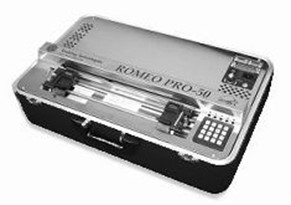

Mr. Hall, the creator of the first braille typewriter, also created templates which made printing braille with print cylinders possible. This was convenient since the machines used to print normal text were also capable of printing braille that way. But when printers became a common part of households – or at least offices – the need for smaller and more flexible braille printers arose. The first printer which was capable of printing text without needing a predefined template and was specialized on braille got released in 1971 by Triformation Systems.

The Romeo braille embosser from Triformation Systems, now called ETC. They produced a whole range of braille embossers, from this Romeo 50cps (braille characters per second), to the high-speed 300cps BraillePlace embosser, and the PED30 braille plate embosser.

Braille printers work much like normal printers in terms of software, but they don’t operate using ink or laser light. They use needles to emboss the letters, one line at a time, on the paper, so they can only print braille and nothing else. To be able to print a document, it first needs to get translated into braille, though. The first commercial braille translation package which did that job already got released in 1976. However, braille printers aren’t nearly as common (or cheap!) as normal printers. So, next time you are mad at your printer for being expensive, refusing to work and constantly claiming to be out of ink, remember it could be worse: You could have to rely on a braille printer.

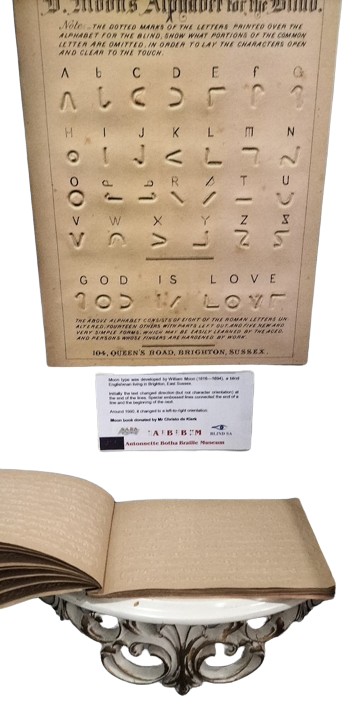

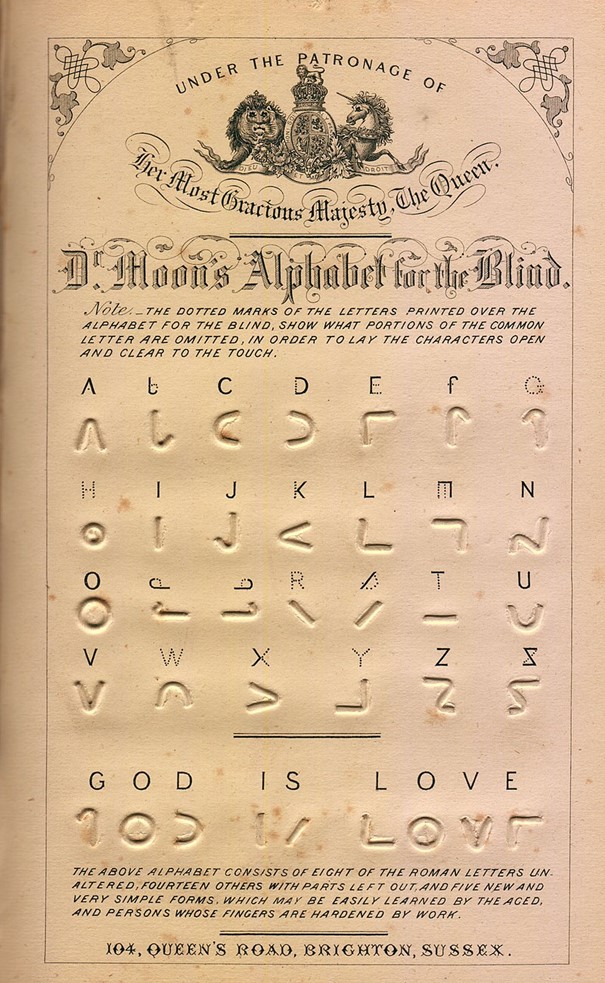

The Moon System of Embossed Reading

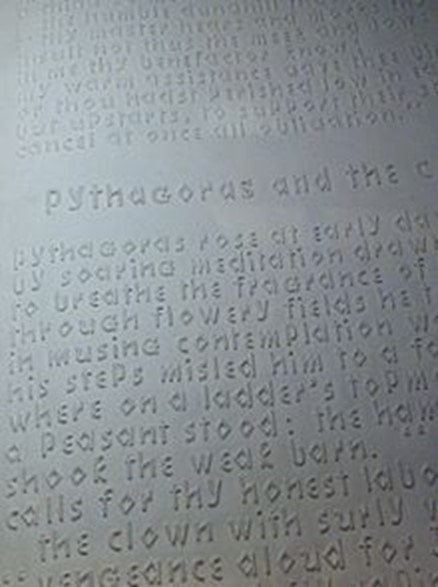

The Moon System of Embossed Reading (commonly known as the Moon writing, Moon alphabet, Moon script, Moon type, or Moon code) is a system of raised shapes, which can help blind people of any age to read by touch.

It is a system of embossed typography for the blind, based on simplified forms of the Latin alphabet. These shapes are rotated or reflected to create the 26 letters of the alphabet and additional dots are used for punctuation marks and the numeral sign.

It was devised by a blind English man, named Dr William Moon

Born: December 18, 1818; in Horsmonden, England

Died: October 10, 1894 (aged 75); in Brighton, England

About Moon

The inventor’s vision was severely damaged by scarlet fever when he was a child and worsened throughout his adolescence, in spite of several surgeries. He was an excellent student and went on to study for the ministry.

After his sight deteriorated to the point of total blindness in 1840, Moon committed himself to teaching other blind people to read by touch, using several existing systems of embossed type available at the time. Two years later he opened a school for the blind in Brighton, England.

An alternative to Braille

Many of his students, especially adults and those who became blind later in life, failed to master the existing systems of embossed script, leading to Dr Moon to invent his system in 1845. Braille – though invented 16 years before – had not reached the UK from France. His first publication appeared in 1847, and from 1850 onwards this script was taught by missionaries in India, China, Egypt, Australia and West Africa.

Dr Moon’s script was thus the first reading system for the blind to be widely adopted across the world, but it was costly to print. It was overtaken by braille in the late 19th century, which was cheaper, and could be produced by blind individuals for themselves.

Easier to learn?

As the characters are fairly large and over half the letters bear a strong resemblance to the print equivalent, Moon has been found particularly suitable for those who lose their sight later in life, or for people who may have a less keen sense of touch.

Some children with additional physical and/or learning difficulties can acquire some literacy skills through learning Moon.

Why isn’t the print alphabet raised?

People often wonder why the standard print alphabet is not raised for use by touch.

This was tried, however because of the complexity of printed letters, it was found that the raised letters had to be made very large to be felt properly. This meant slow reading speeds and with very bulky books, resulted in frustrated readers.

Source: RNIB; Britannica

The Boston Line Letter

Source: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Boston line letter was a tactile writing system created by Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe in 1835, a popular precursor to the now-standardized braille.

Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe, the first director of the New England Asylum for the Blind (now Perkins School for the Blind), studied tactile printing systems in Europe and developed his own system of raised type called Boston Line Letter. Howe’s system was similar to raised letters designed by James Gall in Edinburgh, Scotland, in the 1820s. In 1835 Howe printed Acts of the Apostles, the first book produced in Boston line letter. The letterforms were an angular modification of Roman letters and had no capital letters. The first books embossed at the American Printing House for the Blind in 1866 were in Boston line letter.

By 1868, N.B. Kneass, Jr., a printer in Philadelphia, had adapted what became known as a “combined system” which used the lower case forms of Boston line letter and capital letters from a rival tactile system known as Philadelphia Line. Until replaced by dot systems, this hybrid form of raised letters was the predominant embossed type for blind people in the United States and the choice of most of the schools.

The New York Point

New York Point is a braille-like system of tactile writing for the blind invented by William Bell Wait (1839–1916), a teacher in the New York Institute for the Education of the Blind. The system used one to four pairs of points set side by side, each containing one or two dots. (Letters of one through four pairs, each with two dots, would be ⟨:⟩ ⟨::⟩ ⟨:::⟩ ⟨::::⟩.) The most common letters are written with the fewest points, a strategy also employed by the competing American Braille.

Capital letters were cumbersome in New York Point, each being four dots wide, and so were not generally used. Likewise, the four-dot-wide hyphen and apostrophe were generally omitted. When capitals, hyphens, or apostrophes were used, they sometimes caused legibility problems, and a separate capital sign was never agreed upon. According to Helen Keller, this caused literacy problems among blind children, and was one of the chief arguments against New York Point and in favor of one of the braille alphabets.

New York Point competed with the American Braille alphabet, which consisted of fixed cells two points wide and three high. Books written in embossed alphabets like braille are quite bulky, and New York Point’s system of two horizontal lines of dots was an advantage over the three lines required for braille; the principle of writing the most common letters with the fewest dots was likewise an advantage of New York Point and American Braille over English Braille.

Wait advocated the New York System as more logical than either the American Braille or the English Braille alphabets, and the three scripts competed in what was known as the War of the Dots. Around 1916, agreement settled on English Braille standardized to French Braille letter order, chiefly because of the superior punctuation compared with New York Point, the speed of reading braille, the large amount of written material available in English Braille compared with American Braille, and the international accessibility offered by following French alphabetical order. Wait also invented the “Kleidograph”, a typewriter with twelve keys for embossing New York Point on paper, and the “Stereograph”, for creating metal plates to be used in printing.

Gallery section

DIFFERENT BRAILLE SCRIPTS FROM AROUND THE WORLD

You can make a difference!

By donating to the museums cause you can make a difference in the preservation of Braille’s History.